It’s a diet trend endorsed by everyone from Hollywood A-listers to Rishi Sunak.

Now scientists say intermittent fasting could even be more effective than calorie counting for weight loss.

Slimmers undertaking the 4:3 fast — when calorie intake is restricted for three days in a week — shed more weight than those who limit their calories daily, research has suggested.

Overweight adults who stuck to the part-time regime for a year lost just over a stone on average.

By comparison, calorie restrictors dropped less than half of this weight.

One US academic behind the research said results show fasting too many times a week ‘may be too rigid’ for effective weight loss.

‘We think fasting three days a week might be a sort of sweet spot for weight loss,’ said Victoria Catenacci, the research’s co-lead author and an associate professor at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

‘More fasting days per week may be too rigid and difficult to stick to, while fewer may not produce enough of a calorie deficit to outperform daily calorie restriction diets.’

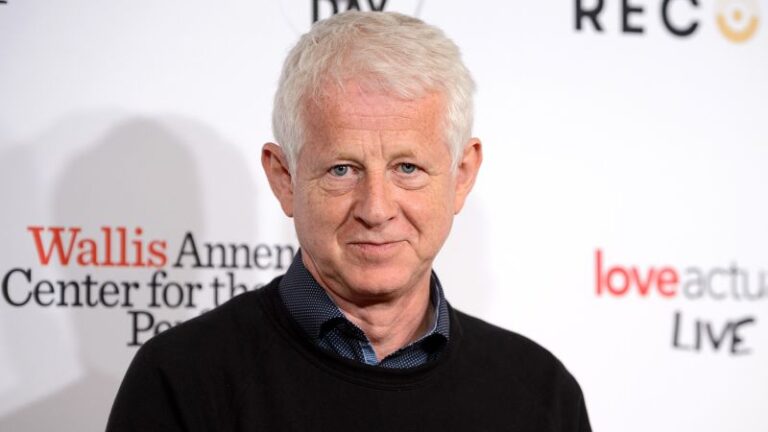

Jennifer Aniston , Chris Pratt and Kourtney Kardashian are among the Hollywood A-listers to have jumped on the trend since it shot to prominence in the early 2010s

Despite swathes of studies suggesting intermittent fasting — which shot to prominence in the early 2010s — does work, experts remain divided over its effectiveness and the potential long term health impacts.

Some argue that fasters usually end up consuming a relatively large amount of food in one go, meaning they don’t cut back on their calories — a known way of beating the bulge.

They even warn that it may raise the risk of strokes, heart attacks or early death.

In the fresh study, researchers examined 165 overweight or obese people and split them into two diet regime groups.

The three-day-a-week fasters — known as the 4:3 group — had to restrict their calories by 80 per cent on their fasting days.

For example, if their baseline was 2,500 calories a day, they would eat roughly 500 calories instead on these days.

Their calorie intake for the remaining four days was not limited, although they were encouraged to make healthy food choices.

The reduced-calorie volunteers, meanwhile, were told to eat around 35 per cent fewer calories than usual each day.

The scientists said those who undertook the 4:3 fast lost 7.6 per cent of their body weight after a year compared to the 5 per cent among those who were calorie counting every day

This meant both groups should have been operating at an equal energy deficit over the course of each week.

The researchers gave all participants behavioural support, free gym membership and encouraged them to exercise for at least 300 minutes per week.

Writing in the journal the Annals of Internal Medicine, the scientists said participants who undertook the 4:3 fast lost 7.6 per cent of their body weight after a year.

This stood at 5 per cent among those who restricted their daily calorie intake.

Adam Collins, associate professor of nutrition at the University of Surrey, said: ‘The study’s main finding was that a 4:3 approach gives more weight loss than conventional calorie restriction, despite participants [being] prescribed the same overall calories.

‘Yet, this is not a magic property of the 4:3 approach per se, but because they achieved a bigger calorie deficit.’

He added: ‘Adherence to any diet over 6-12 months is challenging at the best of times, but this may explain why the 4:3 group were closer to the calorie deficit target overall.

‘Nevertheless, it does support the notion that, in the real world, intermittent energy restriction protocols outperform conventional everyday calorie restriction both in terms of compliance and results.’

Obesity has been well established as increasing the risk of serious health conditions that can damage the heart, such as high blood pressure, as well as cancers.

It has been estimated to cause one in 20 cancer cases in Britain, according to the Cancer Research UK.

Britain’s obesity crisis is also estimated to cost the nation nearly £100billion per year.

This colossal figure includes the health harms on the NHS as well as secondary economic effects like lost earnings from people taking time off work due to illness and early deaths.

Experts have blamed the nation’s ever-expanding waistline on the simultaneous rise of processed, calorie-laden food and sedentary, desk-bound lifestyles.